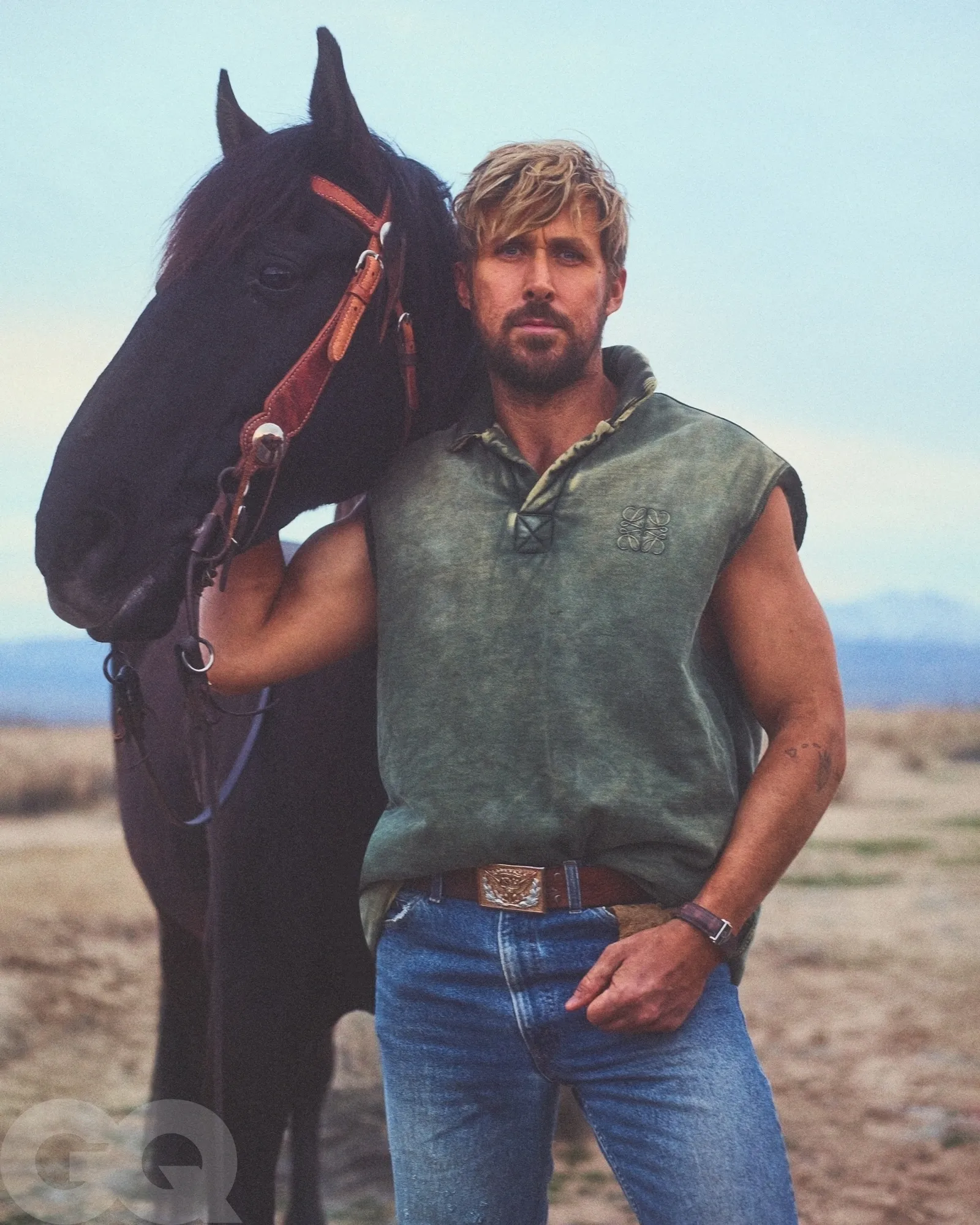

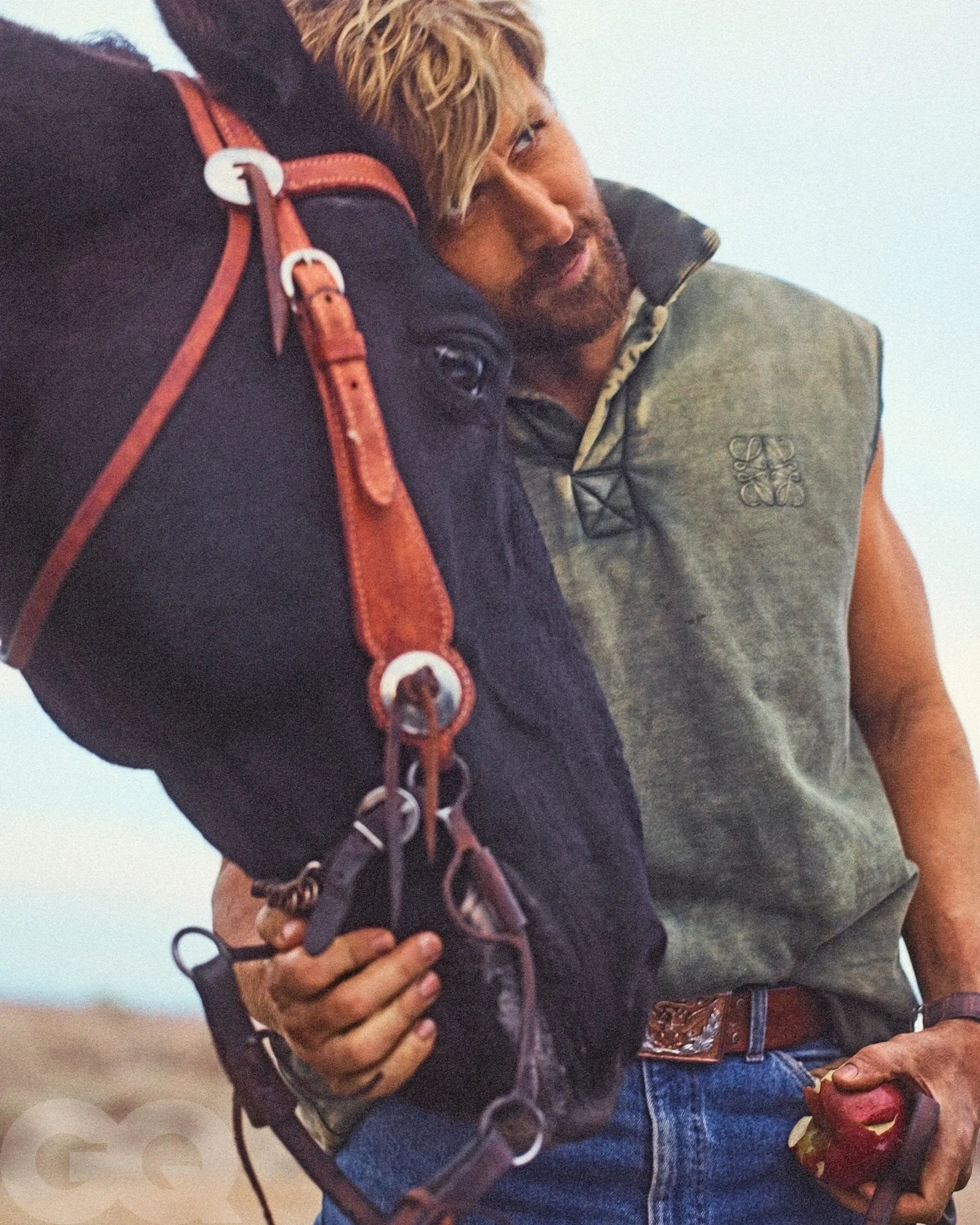

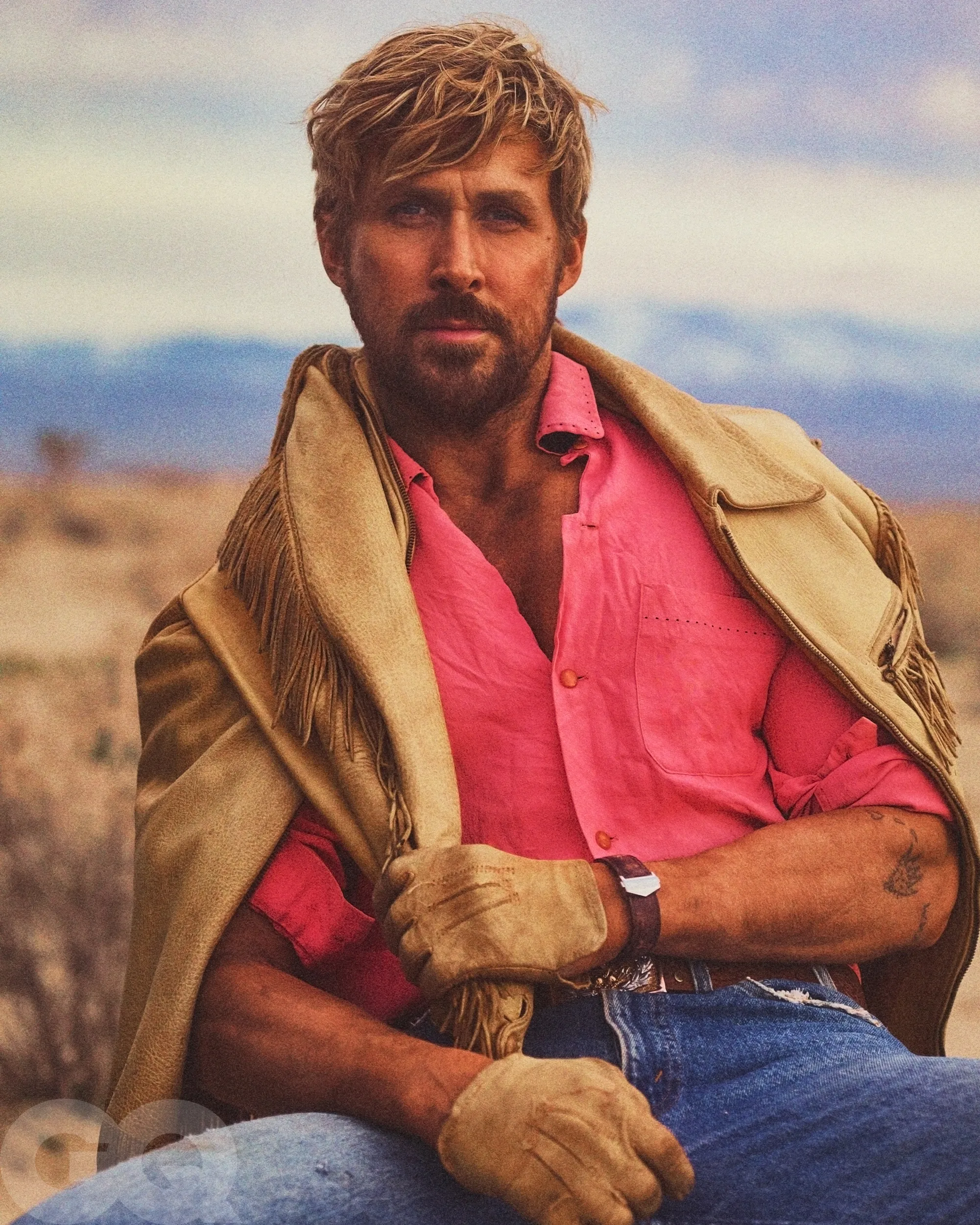

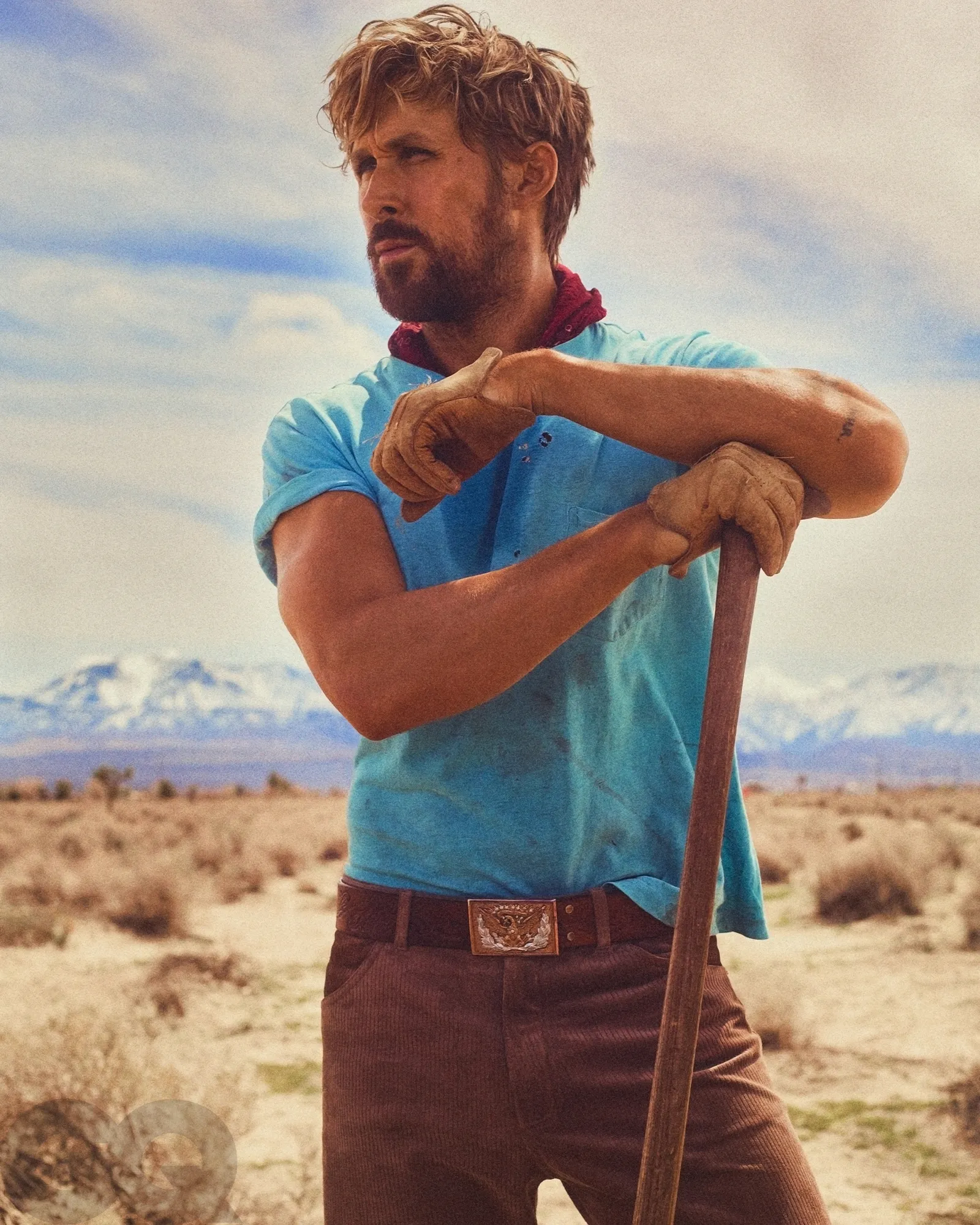

What Ken't Ryan Gosling Do?

- Polo Lifestyles 2020

- Sep 7, 2023

- 5 min read

As he ventured back into the spotlight to play Ken in the summer blockbuster Barbie, Ryan Gosling talked candidly about why he stepped away from Hollywood, why he’s thinking about movie-making differently now, and why he’s prioritizing the off-screen roles he plays in real life.

Story By Zach Baron / Photography by Gregory Harris / Edited by Josh Jakobitz

Ryan Gosling subscribes to what he calls an escape-room style of being an actor. This is a little theoretical, because he’s never actually been to an escape room, and he’s not totally sure what happens inside of them.

“Maybe I should do one,” he says, “to see if this really works.” But the general idea is: You’re thrown into a particular set of circumstances and you’ve got to find your way out. Maybe you show up on set one day and it’s raining when it’s not supposed to be raining, Gosling says, “or this person doesn’t want to say any of that dialogue, or the neighbor’s got a leaf blower and they’re not turning it off.” What do you do next?

Over time, Gosling has discovered that this approach might apply to more than just acting. Maybe, for instance, you’re a kid growing up in a town you don’t want to be in and you’re trying to locate an exit. Maybe you’re looking for something you can’t put into words and you make movies to try to pin down whatever it is you’re looking for. Maybe you’re a person who never envisioned raising a family and then you meet the person who changes, in some radical way, how you see yourself and your future. Life comes at you, in all its unanticipated and startling particulars; the thing that makes you an artist is the way you respond.

And being open to the unexpected has served Gosling well. When he was young, his first real breakthrough came in a movie, 2001’s The Believer, about a Jewish kid from New York who becomes a neo-Nazi. Gosling was none of these things, a fact that the director, Henry Bean, turned out to like—“The fact that I wasn’t really right for it was exactly why he thought I was right for it,” Gosling says. A few years later, when Gosling was auditioning for The Notebook, he says, the director, Nick Cassavetes, “straight up told me: ‘The fact that you have no natural leading man qualities is why I want you to be my leading man.’ ” Gosling got the part; he’s been a leading man ever since.

In his youth, Gosling treated acting a little bit like therapy, or an opportunity “to teach myself about myself.” He was in search of experiences—films that could capture a mood, or a feeling. Sometimes what he was doing barely looked like acting at all. “Even though I think Ryan has watched a lot of movies, the way he acts is as if he hasn’t watched that many movies,” Emily Blunt, who first got to know Gosling on the set of David Leitch’s forthcoming movie The Fall Guy, says. For 2010’s Blue Valentine, Gosling lived for a time with his costar, Michelle Williams, in the house where they shot the film, playing the part of parents with the young actor who played their daughter. For 2011’s Drive, he and the film’s director, Nicolas Winding Refn, spent days driving across Los Angeles, listening to music, whittling away dialogue from their script until the film was purely about the unnameable sensation the two of them shared in the car. “I was trying to find a place to put all these things that were happening to me,” Gosling says. “And these films became ways to do that, like time capsules.” For Only God Forgives, Refn’s next film, Gosling spent months in Thailand before shooting began, training in Muay Thai camps, learning to fight.

“And I don’t think I did Muay Thai once in that film,” Gosling says. Refn changed plans. Gosling was okay with it. “I didn’t do the film to do Muay Thai,” he says.

And then something interesting happened, or maybe—in the manner of life—a few things happened, and the way Gosling worked began to change. In 2014, he and his partner, Eva Mendes, with whom he starred in The Place Beyond the Pines, had their first kid, and then in 2016, their second, both daughters. Gosling started to act in fewer independent movies and more studio films, like La La Land and Blade Runner 2049. These were movies, as Gosling describes them to me, “for an audience.” And then, for four years, he didn’t appear in anything at all.

Gosling’s explanation for his absence from Hollywood is straightforward: He and Mendes had recently had their second kid, “and I wanted to spend as much time as I could with them.” Gosling is not one of those people who pictured himself as a parent—the moment he first imagined himself as a father, he says, was the moment immediately before he became one: “Eva said she was pregnant.” But, he adds, “I would never want to go back, you know? I’m glad I didn’t have control over my destiny in that way, because it was so much better than I ever had dreamed for myself.”

When Gosling finally came back to work, it was for last year’s The Gray Man, an action spectacle directed by the Russo brothers for Netflix, and then this year’s Barbie, directed by Greta Gerwig. He says the time away solidified certain changes in his attitude toward his job. “I treat it more like work now, and not like it’s, you know, therapy,” he says. “It’s a job, and I think in a way that allows me to be better at it because there’s less interference.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, the projects he’s gravitating toward now, which include another giant action film, The Fall Guy—which Leitch describes as “a love letter to big movies,” and which Gosling just finished shooting in Australia—seem to have larger and more crowd-pleasing aspirations. “I’ve always wanted to do it,” Gosling says. “I just never really had the opportunity like this, or it never kind of worked itself out this way. It took me a long time to get into sort of bigger, more commercial films. I had to kind of take the back entrance.”

When Gosling was younger, making independent movies, it was often with the unspoken expectation that not many people would see them. “So you kinda make the movie for yourselves,” he says. Somebody had once given him the advice: Your job is just to feel it. “Doesn’t matter if anyone else does, you know?” Gosling says. “But I think, having done a lot of that, I realize that I kind of feel like my job is for other people to feel it. And it’s cool if I do, but that’s really not the point. The point is that other people do.”

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

蜘蛛池 蜘蛛池;

谷歌马甲包/ 谷歌马甲包;

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏;

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏

蜘蛛池 蜘蛛池

谷歌快排 谷歌快排

Google外链 Google外链

谷歌留痕 谷歌留痕

Gái Gọi…

Gái Gọi…

Dịch Vụ…

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏

负面删除 负面删除

币圈推广 币圈推广

Google权重提升 Google权重提升

Google外链 Google外链

google留痕 google留痕

AV在线看 AV在线看;

自拍流出 自拍流出;

国产视频 国产视频;

日本无码 日本无码;

动漫肉番 动漫肉番;

吃瓜专区 吃瓜专区;

SM调教 SM调教;

ASMR ASMR;

国产探花 国产探花;

强奸乱伦 强奸乱伦;

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

谷歌蜘蛛池 谷歌蜘蛛池;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

谷歌权重提升/ 谷歌权重提升;

谷歌seo 谷歌seo;

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏

蜘蛛池 蜘蛛池

谷歌快排 谷歌快排

Google外链 Google外链

谷歌留痕 谷歌留痕

Gái Gọi…

Gái Gọi…

Dịch Vụ…

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏

负面删除 负面删除

币圈推广 币圈推广

Google权重提升 Google权重提升

Google外链 Google外链

google留痕 google留痕

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

谷歌蜘蛛池 谷歌蜘蛛池;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

谷歌权重提升/ 谷歌权重提升;

谷歌seo 谷歌seo;

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏

蜘蛛池 蜘蛛池

谷歌快排 谷歌快排

Google外链 Google外链

谷歌留痕 谷歌留痕

Gái Gọi…

Gái Gọi…

Dịch Vụ…

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏

负面删除 负面删除

币圈推广 币圈推广

Google权重提升 Google权重提升

Google外链 Google外链

google留痕 google留痕

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

游戏推广 游戏推广;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

谷歌马甲包/ 谷歌马甲包;

谷歌霸屏 谷歌霸屏;

מכונות ETPU מכונות ETPU;

;ماكينات اي تي بي…

آلات إي بي بي…

ETPU maşınları ETPU maşınları;

ETPUマシン ETPUマシン;

ETPU 기계 ETPU 기계;